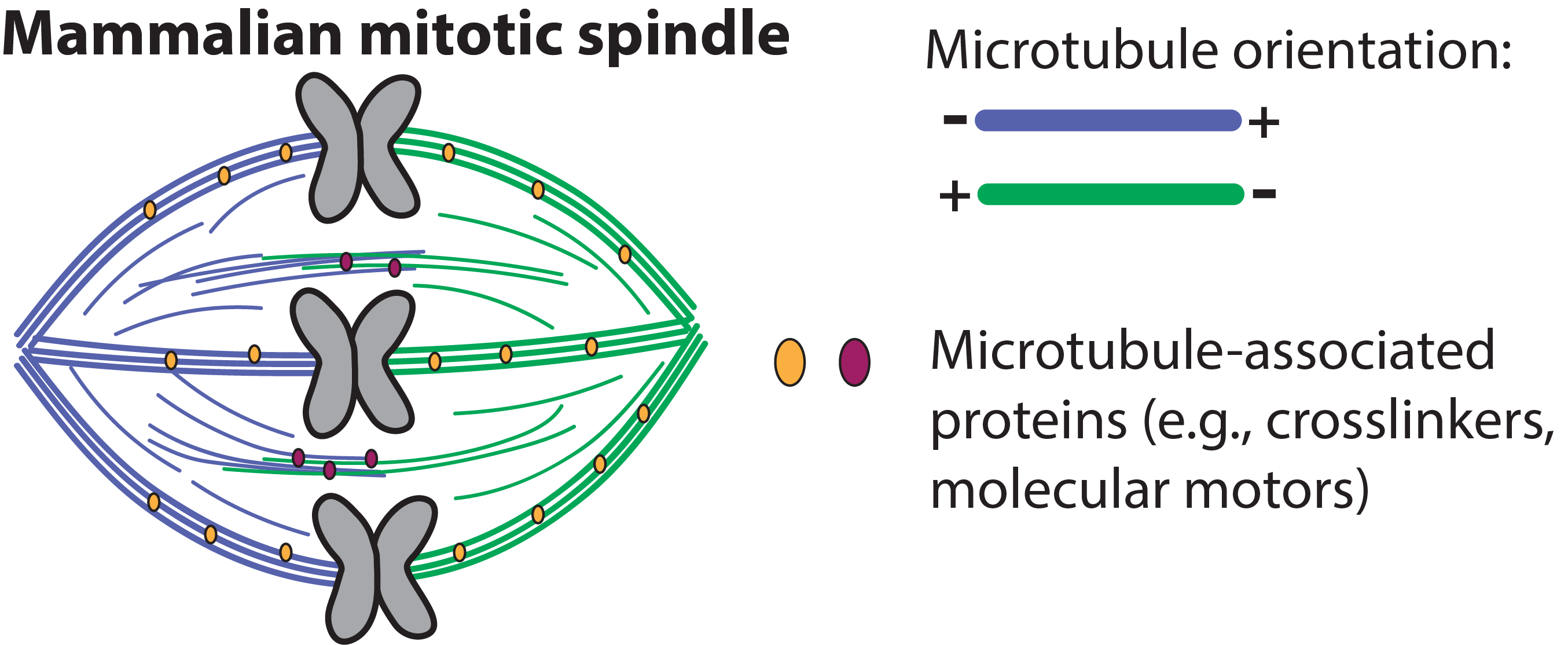

From molecules to organisms, biological form follows function. The Elting Lab is interested in how biological molecules self-organize into cellular-scale structures that perform essential mechanical roles. In particular, we are fascinated by the microtubule (MT) cytoskeleton, whose long, geometrically polarized tubulin filaments assemble into diverse architectures that give eukaryotic cells their shape, structure, and organization. For instance, radial arrays direct cargo transport; axon bundles impart orientation and stiffness; and the mitotic spindle, a microtubule-based machine, delivers chromosomes to two daughter cells.

To ask how these structures self-organize and perform their mechanical tasks, we apply an interdisciplinary approach that combines tools and approaches from physics, biology, chemistry, and engineering. At its core, our mentality is summarized by this quote, written on Richard Feynman’s blackboard when he died:

"What I cannot create, I do not understand."

For us, this means combining an in vitro synthetic engineering approach with perturbations in live cells, allowing us to test hypotheses of cytoskeletal assembly and mechanics. We envision recreating complex microtubule architectures in vitro, modeling them in silico, and changing their assembly in vivo, to better understand and control nature’s structures.

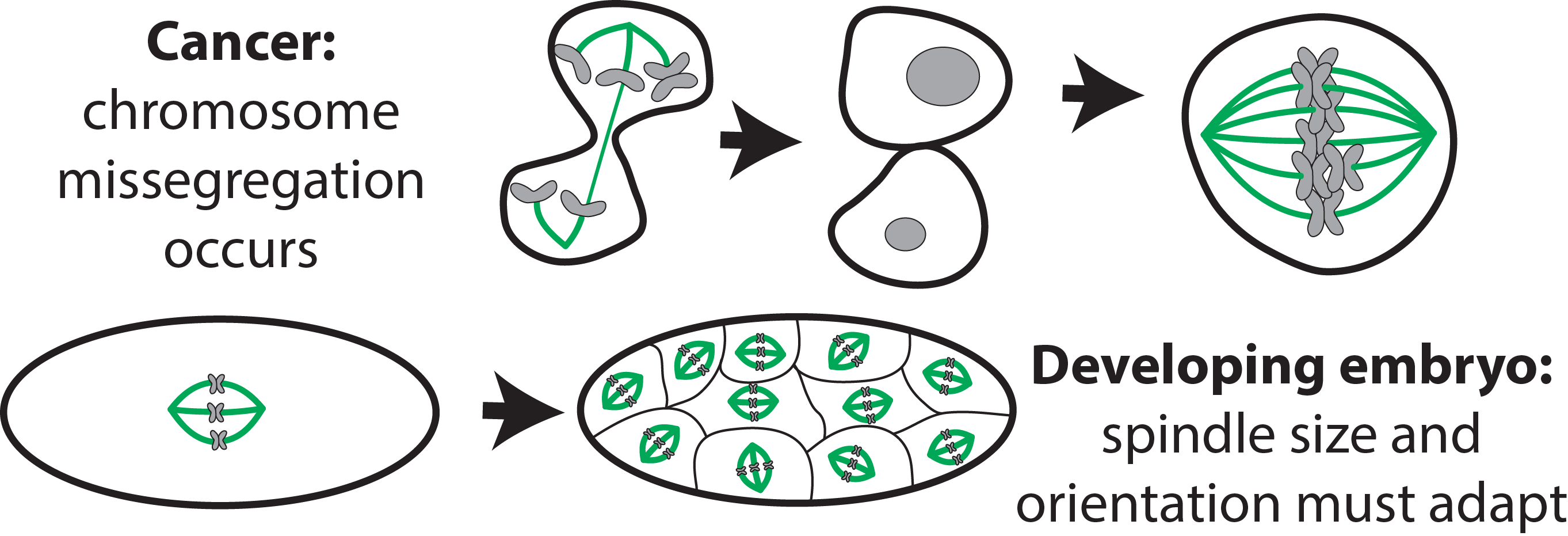

The mitotic spindle is one of the most complex microtubule architectures the cell builds, and its function is crucial. As the machine that segregates genetic material, errors in spindle function lead to extra or missing chromosomes, causing developmental defects or cancer. During development, spindles must accommodate changing cellular length scales and orient properly for tissue patterning. Cancer cells divide more frequently and face the mechanical challenge of crowding from extra chromosomes, making the spindle a potentially rich target for therapy.

While we have a long “parts list” of spindle proteins, we do not understand how these parts assemble to give the spindle its cellular-scale architecture and function. In the Elting lab, we test how specific molecular interactions give rise to micron-scale microtubule structures that underpin spindle architecture, but are not well-described mechanically. Thus, we ask how biochemistry and architecture feedback to control spindle function.

To answer these questions, we need new tools, which we are now developing, for controlled perturbations of mechanics and architecture inside cells. These will allow us to combine high-resolution fluorescence imaging with targeted mechanical and genetic perturbations, quantitative image analysis, and physical modeling. As experimental systems, we use the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe, whose simple, stereotyped spindles provide an ideal bridge from a purified system to one in vivo, and spindles in mammalian cells, including cancer cells, which will help connect our findings more closely to human health. In the long run, we also plan we to connect these lives cell experiments to in vitro reconstitution of microtubules and other spindle components.